Watches

-

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

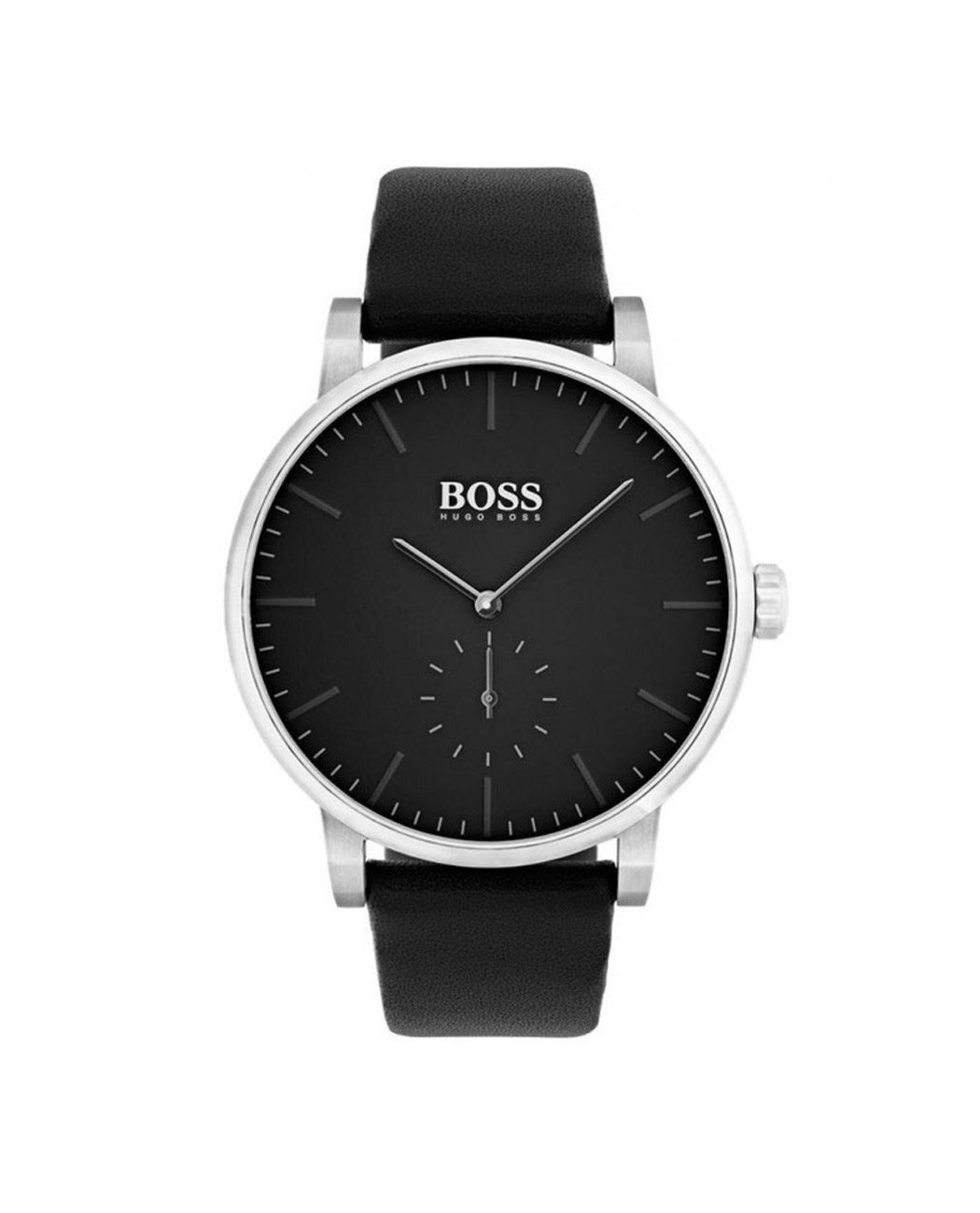

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistBlack Silver Lakeville

$245.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistBold Brown Grant Adventure

$380.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistClassic Dark Essence

$1,250.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

Classic Light Elegant

Original price was: $450.00.$430.00Current price is: $430.00. Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistDark Anthracyte Barstow Front

$660.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistDark Machine Brown

$450.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistMinimal Classic Signatur

$680.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

Modern Blue Brown Style

Original price was: $850.00.$750.00Current price is: $750.00. Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistModern Cherry Watch

$240.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

Modern Skw Brown

Original price was: $460.00.$440.00Current price is: $440.00. Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist

The product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlistSilver Light Brown Ferndale Front

$330.00 Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist -

Skin Black SKW Front

Original price was: $675.00.$620.00Current price is: $620.00. Add to cartThe product is already in your wishlist! Browse wishlist